~ Section 6 – The Birth of Modernism, Styles & Epochs of Art ~

“Design as Vision: Geometry, Function, and the Machine Age”

Between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, art and landscape architecture entered a radical transformation. The Modernist era broke from ornament and historical imitation, embracing abstraction, efficiency, and social progress.

Machines, industry, and urbanization reshaped perception — and designers began to see landscape not as decoration, but as a living framework for modern life.

The Birth of Modernism signaled a new relationship between human, nature, and technology — a search for purity of form, honest materials, and universal order.

© This article references early LASD Studio, Yura Lotonenko white-paper research (2011 – 2017) exploring intersections between Art and Landscape Philosophy

Video Episode of Section 6 — The Birth of Modernism

In this episode of Styles & Epochs of Art that Influenced Landscape Architecture and Garden Design, we explore the Modernist revolution — how art, architecture, and landscape fused into a single design language.

From the purity of Le Corbusier’s geometry to the organic fluidity of Frank Lloyd Wright and the social visions of modern parks, The Birth of Modernism traces how form followed function — and how function reconnected with nature.

The Epoch Overview

Historical & Cultural Context

The Modernist movement emerged amid industrial progress, war, and social change. Artists and designers sought clarity and rational order after the emotional chaos of Romanticism. The machine became a symbol of human potential and discipline — inspiring architects and landscape architects to reimagine space for a new society.

World’s Fairs, Bauhaus theories, and the emergence of urban planning defined a new functional aesthetic: light, air, and movement as the new ornament.

Fine Art & Aesthetic Principles

Modernist painters like Piet Mondrian, Kazimir Malevich, and Wassily Kandinsky reduced nature to geometry and color relationships — an abstract language of balance and tension.

In landscape architecture, these ideas manifested through grids, planes, and minimal planting compositions — space as a sculptural medium.

Movement and function replaced decoration; truth to materials replaced illusion.

Influence on Early Landscape Thought

Designers like Garrett Eckbo, Dan Kiley, and Thomas Church translated Modernist art into living terrain. Their work introduced the concept of “outdoor rooms,” fluid pathways, and dynamic relationships between architecture and landscape.

Nature was no longer a backdrop — it became an active partner in human habitation.

Key Artists, Philosophers & Landscape Architects

Mondrian, Kandinsky, Malevich, Klee & Rothko — The Language of Abstraction

In the early 20th century, a profound artistic revolution unfolded — color, geometry, and emotion became new instruments of truth.

Painters like Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Paul Klee, Piet Mondrian, and later Mark Rothko broke away from representation to reveal the invisible structure of life — rhythm, energy, and spiritual resonance.

Each artist transformed nature into essence — an approach that deeply influenced Modernist landscape architecture and the way we perceive form, void, and color in outdoor space.

Kandinsky saw painting as “visual music.” His Composition 8 (1923) expressed harmony through motion — an orchestration of geometric tension that mirrored the dynamic forces of ecosystems and urban life.

Malevich, through his Suprematist Composition: White on White (1918), pursued absolute reduction — the stillness of infinite space. His vision of pure abstraction echoed in the Modernist use of open planes and minimal surfaces.

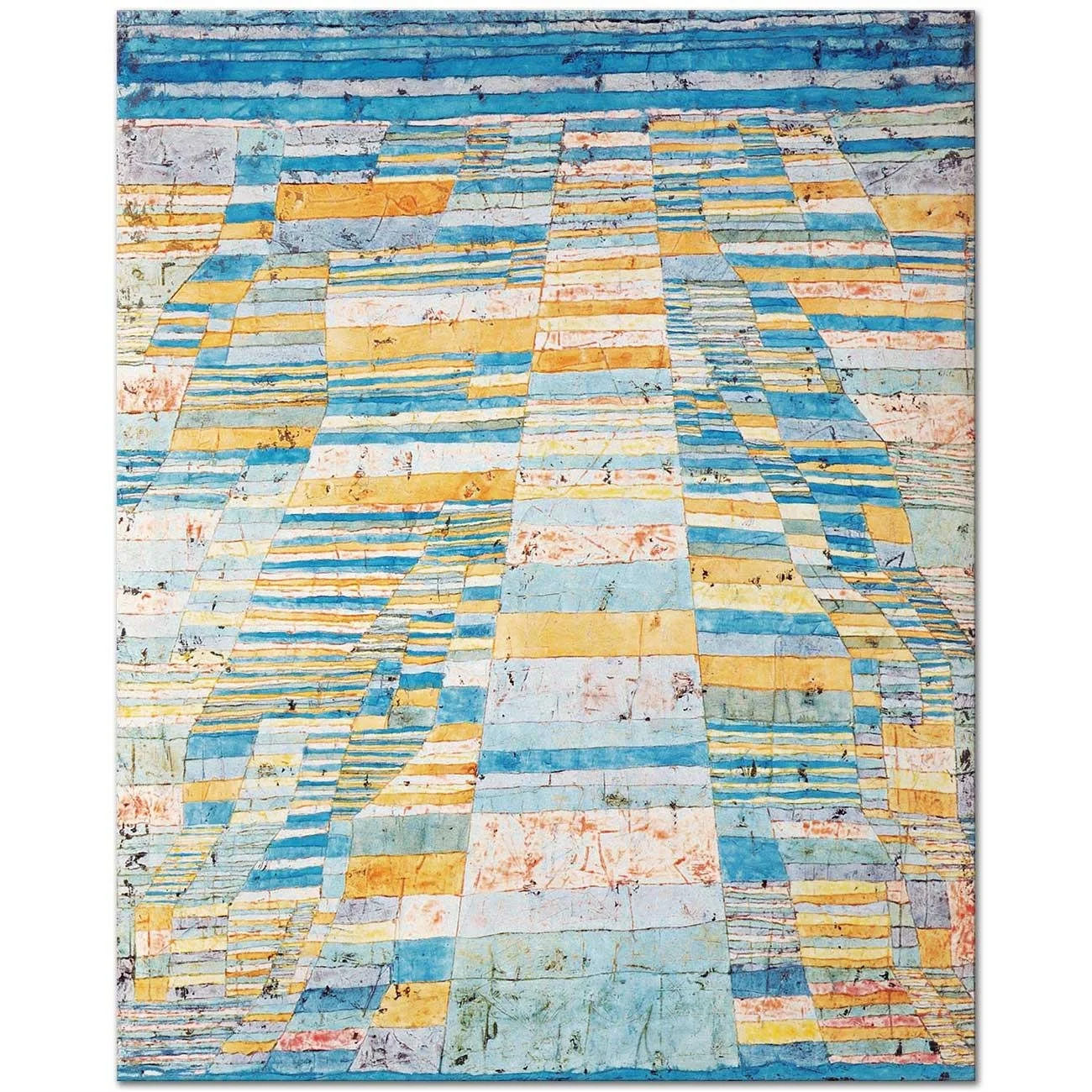

Paul Klee’s poetic abstraction — as in Highway and Byways (1929) — interpreted landscape as movement and pattern, a dialogue between intuition and structure. His work resonates with contemporary mapping, zoning, and ecological layering.

Piet Mondrian sought universal balance in his Composition in Red, Blue and Yellow (1930) — grids and primary colors as living order, where simplicity becomes spiritual clarity. His vision translated directly into Modernist paving layouts, modular gardens, and architectural rhythm.

Finally, Mark Rothko, in No. 61 (Rust and Blue) (1953), carried abstraction into pure emotion — vast color fields evoking light, silence, and transcendence. His meditative atmosphere foreshadowed minimalist gardens and contemplative landscapes of the late 20th century.

Together, these artists revealed that abstraction was not the rejection of nature, but its deeper understanding — a language of proportion, emotion, and essence that continues to guide contemporary ecological and spatial design.

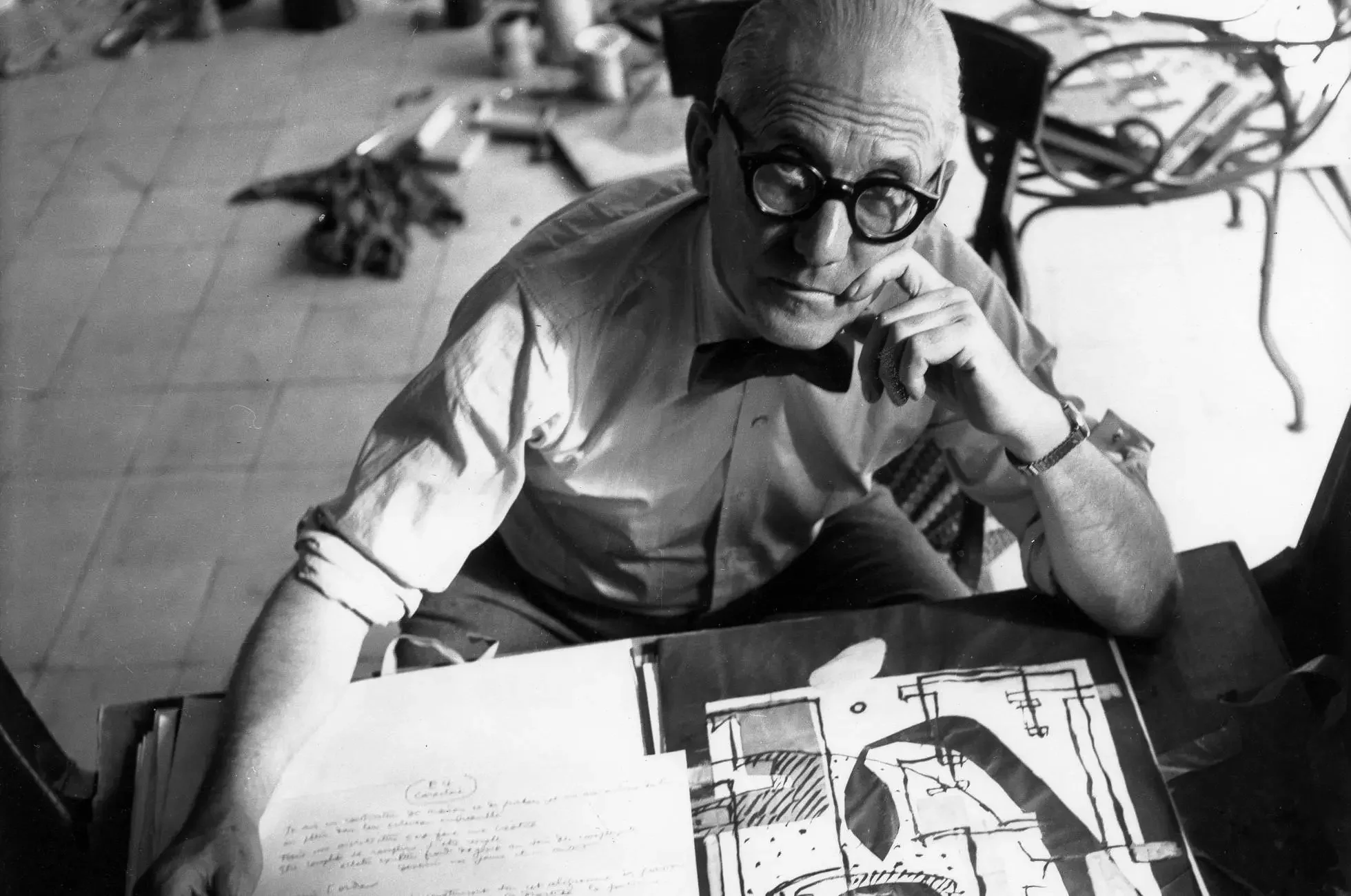

Le Corbusier — The Architect of Purity

Le Corbusier’s “Five Points of Architecture” redefined space as open, light, and modular. His gardens were extensions of buildings, structured by terraces, ramps, and views framed by geometry and shadow.

Frank Lloyd Wright — Organic Architecture

In the early 20th century, Frank Lloyd Wright redefined the relationship between architecture, landscape, and the human spirit.

His philosophy of Organic Architecture called for harmony between building and environment — structures that grow from their sites, shaped by topography, light, and materials drawn from nature itself.

Wright rejected imitation of European styles and instead sought an authentic American modernism rooted in geometry, honesty, and fluid spatial flow.

Through designs like Fallingwater in Pennsylvania and Taliesin West in Arizona, he demonstrated that a home could be both shelter and sculpture — a living organism attuned to the rhythm of water, rock, and sun.

Every line, wall, and terrace in Wright’s work carried ecological intention long before sustainability became a movement.

Stone, timber, and concrete merged seamlessly; cantilevers and horizontal planes echoed the horizon; interiors opened into gardens through continuous glazing and terraces.

This integration of structure and nature influenced generations of modern architects and landscape designers, including Dan Kiley, Garrett Eckbo, and Thomas Church, who extended Wright’s organic vision into the language of open space.

For LASD Studio, Wright’s legacy remains deeply relevant today. His union of form, ecology, and emotion anticipates our own pursuit of Evolutionary Intelligent Landscapes — adaptive systems where design learns from the site itself.

Wright’s Organic Architecture was never a style, but a belief: that beauty arises from balance, proportion, and the living connection between human life and the earth.

Garrett Eckbo, Dan Kiley, and Thomas Church — Modern Landscape Pioneers

In the mid-20th century, three designers reshaped how humans inhabit open space.

Garrett Eckbo, Dan Kiley, and Thomas Church translated the clarity of Modernist art into living terrain — landscapes of movement, human scale, and social purpose.

Their work bridged architecture, ecology, and daily life, turning the post-war garden into a democratic, fluid environment.

Garrett Eckbo introduced a new social dimension to landscape design. His book Landscape for Living (1950) envisioned parks, campuses, and urban plazas as extensions of civic freedom.

Projects such as Los Angeles Union Bank Square used sculptural planting, water, and geometry to express modern optimism.

Dan Kiley refined the Modernist language into a dialogue between order and nature. His Miller Garden in Indiana juxtaposed architectural grids with living canopies of trees, creating spatial rhythm through light and shadow.

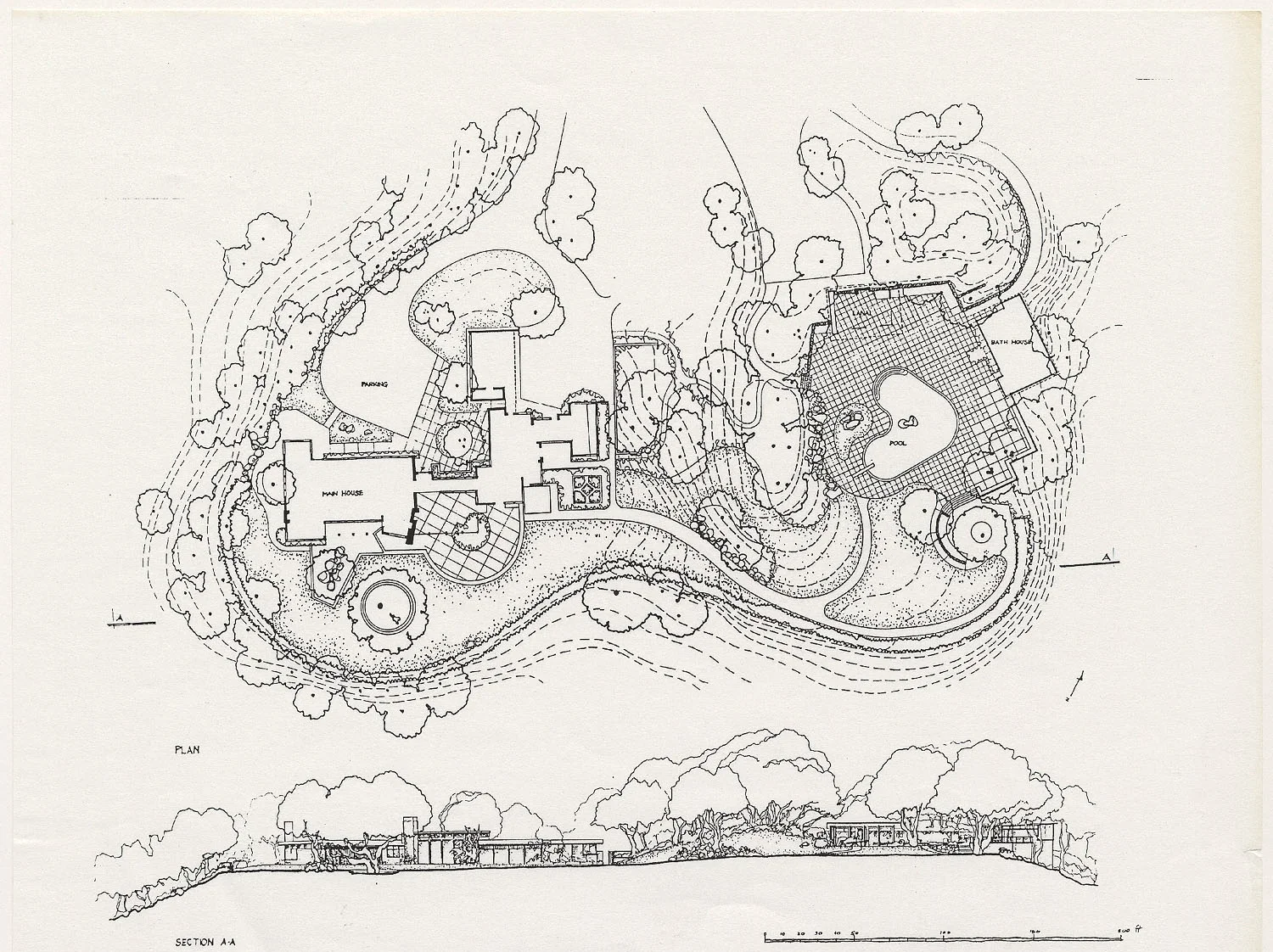

Thomas Church, working in California, humanized Modernism through comfort, informality, and flow. His Donnell Garden merged biomorphic pools and sculptural terraces with the surrounding landscape — a model for the indoor-outdoor lifestyle that defines contemporary design.

Together, they redefined landscape architecture as functional art for modern life, where geometry, vegetation, and human experience coexist as one evolving organism.

Main Landscape Architectural Features of the Epoch

Design Principles

Modernist landscapes favored clarity of space, modular proportion, and functional use. Water became a reflective surface of minimal expression; paving and planting defined geometry rather than ornament.

Key ideas: function as beauty, space as sculpture, and light as material.

Materiality & Plant Palette

Materials included concrete, steel, glass, and stone in their honest form. Plant palettes were restrained — grasses, sculptural trees, and monochrome foliage emphasizing form over color. Nature was curated for structure and rhythm.

Evolutionary Interpretation

For LASD Studio, Modernism marks the beginning of ecological rationalism — seeing design as a system rather than a style.

We reinterpret this legacy as Evolutionary Intelligence: clarity with complexity, precision with adaptation. Our projects extend Modernism’s discipline into living, responsive environments that breathe, learn, and evolve over time.

LASD Studio Interpretation & Works

Designing Landscapes as Evolutionary Systems

At LASD Studio, we continue the Modernist tradition of clarity and innovation — not as rigid form, but as living order. Our Evolutionary Intelligent Systems merge functional design with ecological processes, where each plan evolves like a biological grid — adapting to climate, use, and time.

Every project we create honors the Modernist ideal of truth to materials — and adds a new layer of ecological intelligence, where geometry meets growth and the machine learns from nature.